Goddesses of Akragas

A Study of Terracotta Votive Figurines from Sicily

Gerrie van Rooijen | 2021

Goddesses of Akragas

A Study of Terracotta Votive Figurines from Sicily

Gerrie van Rooijen | 2021

Paperback ISBN: 9789088909009 | Hardback ISBN: 9789088909016 | Imprint: Sidestone Press Dissertations | Format: 210x280mm | 388 pp. | Language: English | 5 illus. (bw) | 250 illus. (fc) | Keywords: classical archaeology; figurines; coroplastics; terracotta; votives; Sicily; archaeological experiment; moulding techniques; migration | download cover

Read online or downloaded 305 times

-

Digital & Online access

This is a full Open Access publication, click below to buy in print, browse, or download for free.

-

Buy via Sidestone (EU & UK)

-

Buy via our Distributors (WORLD)

For non-EU or UK destinations you can buy our books via our international distributors. Although prices may vary this will ensure speedy delivery and reduction in shipping costs or import tax. But you can also order with us directly via the module above.

UK international distributor

USA international distributor

-

Bookinfo

Paperback ISBN: 9789088909009 | Hardback ISBN: 9789088909016 | Imprint: Sidestone Press Dissertations | Format: 210x280mm | 388 pp. | Language: English | 5 illus. (bw) | 250 illus. (fc) | Keywords: classical archaeology; figurines; coroplastics; terracotta; votives; Sicily; archaeological experiment; moulding techniques; migration | download cover

Read online or downloaded 305 times

We will plant a tree for each order containing a paperback or hardback book via OneTreePlanted.org.

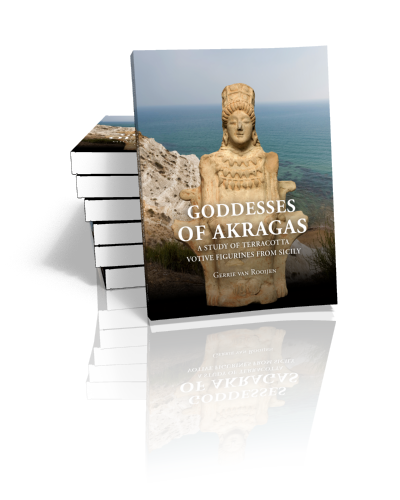

The terracotta figurines from Akragas (Agrigento) with their chubby faces, splendid furniture, and rich adornments, depict a prosperous life in the late sixth and early fifth century BCE. The extensive jewellery on the figurines contains strikingly large fibulae appliques fastening pectoral chains with several sorts of pendants. They are modelled after existing items. The form of the jewellery items changed fast, influenced by different peoples and changing fashions, which can be compared with representations of jewellery and fashion on coins of the same period from Syracuse.

In contrast, the body of the figurines remained armless and abstract for some time, nor does it express its gender. The block shaped, sloping upper body might have originated with aniconic objects, but suggests here a seated person, covered with a rectangular apron on the front. In contrast, the face is detailed, and often crowned with a specific headgear, the polos. The Archaic smile reveals Greek influence on its features.

An archaeological experiment in which figurines and moulds were reproduced revealed their production process. By combining data from the experiment with an analysis of their iconographic features, most of the figurines studied can be shown to have been designed and produced locally. The moulding technique, introduced by newcomers to the city, provided for relatively cheap and rapid production of terracotta figurines. Local clay and marl are found near to the city, and its composition was found to be very suitable, due to its plasticity, fine structure and soft tone on firing.

Wooden figurines, the forerunners of the terracotta figurines, were used in the production of the moulds of their terracotta successors. The terracotta figurines developed to become more three-dimensional, so that they were able to stay upright unsupported. Objects and moulds were exchanged with the city of Selinous, resulting in variations of the standard and figurines with finely detailed faces.

Designing and dedicating these votive figurines, and possibly also jewellery, to a cult statue might have acted as a unifying element for the perhaps multi-ethnic society of Akragas. By means of these anthropomorphic female figurines, people gave shape to their origin and narratives, using old and new symbols such as the Phoenician crescent and the Greek satyr. Their cultural influences formed a new religious setting, helping to forge a new identity unique to Sicily. The prosperity expressed by these metal adornments, fits Diodorus Siculus’ description of Akragas as a rich city.

List of figures with references

I Akragantine figurines and their context

I.1 Introduction

I.2 State of research

I.2.a Identifying the figurine and the dedicants

I.2.b Proving literature right by the archaeological material

I.2.b.i Cult transfer and a prototype reconstruction

I.2.c Athena Lindia? Rhodian and Sicilian figurines compared

I.2.d Other views on identification and origin

I.2.e Oikist cult and cultural identity formation

I.2.f Intermarriage and gender

I.3 Aims and research questions

I.4 Method and archaeological theory

I.5 Research structure

I.6 Greek historiography on Sicily – some general remarks

I.6.a Mythical past

I.6.b Political setting

I.6.b.i The perception of ancient authors

I.6.b.ii Sicily in the account of Thucydides

I.6.b.iii The foundation of Gelas and Akragas

I.6.b.iii.1 Gelas

I.6.b.iii.2 Herodotus on Gelas

I.6.b.iii.3 Akragas

I.6.b.iii.4 Herodotus on Theron of Akragas

I.6.c Social and economic setting

I.6.c.i Diversity among the inhabitants of Sicily

I.6.c.ii Phoenicians

I.6.c.iii Prosperity of Akragas

I.6.d Religious setting

I.6.d.i Demeter and Persephone on Sicily

I.6.d.ii Temple building and politics

I.6.e Conclusions on the ancient literary sources

II Iconography of the figurines

II.1 Introduction

II.2 Aims

II.3 Method

II.4 The body

II.4.a The local tradition

I.4.a.i Arms and feet

II.4.b Imported and imitated images

II.4.c Upright

II.4.d From wood to terracotta

II.4.e An aniconic tradition

II.4.f Gender

II.4.g Practical implications of the figurines’ form

II.4.h The form of the figurines and their role as votives

II.5 Head and face

II.5.a General shape and expression of the face

II.5.b A personal expression

II.5.c Cultural influences

II.5.c.i Noses

II.5.c.ii Mouth and chin

II.5.c.iii Eyes

II.5.c.iv Ears

II.5.c.v Hair

II.5.d Gender

II.6 Dress and personal adornment

II.6.a The apron

II.6.b Non-Sicilian garments

II.6.b.i The undergarment

II.6.c Cultic dress

II.6.d Footwear

II.6.e Headgear

II.6.e.i Veil

II.6.e.ii Polos

II.6.e.iii The meaning of the polos and veil

II.6.e.iii The headdress as an indication of marital status

II.6.f Fibulae

II.6.f.i Interpretation and comparison with real-life objects

II.6.g Pectoral bands and pendants

II.6.g.i Akragantine pendants

II.6.h.ii Linked to the locals: pectoral bands

II.6.h.iii Discs and crescents

II.6.h.iv Figurative pendants

II.6.h.v Other beads and pendants with their real-life counterparts from other sites

II.6.h.vi Comparison with other cultures

II.6.h.vii Cultural exchange

II.6.h.viii Function and meaning

II.6.h Other jewellery

II.6.h.i Ear studs and earrings

II.6.h.ii Bracelets

II.6.h.iii Necklaces and hairbands

II.6.h.iv Comparison with korai jewellery

II.6.i Gender, identity and the display of wealth

II.7 Furniture

II.7.a From bench to throne

II.7.a.i The footstool

II.7.b The origin of the represented chair shapes

II.7.b.i Greek chairs: thronos and klismos

II.7.b.ii Thrones and lions

II.7.b.iii An enthroned couple

II.7.c Gender and identity

II.8 Conclusions

III The technology of Akragantine figurines

III.1 Introduction

III.2 Aims of technical research

III.3 Method: An archaeological experiment with analogue reconstruction

III.4 Interpretation and the chaîne opératoire approach

III.5 The general production process

III.5.a Object categories

III.5.b Solid objects and plaques

III.5.c Description of the steps in the production process

III.6 The coroplastic experiment

III.7 Results of the experiment and comparison with features of the original objects

III.7.a Step 1: The clays used in Akragas

III.7.b Steps 2 and 3: Choice of patrix and creating the matrix

III.7.c Step 4: Aspects of the shaping process and related items

III.7.c.i Making the front of the figurine

III.7.c.ii Making the back of the figurine

III.7.c.iii Making an extra rim

III.7.c.iv Drying and deformation

III.7.c.v The derivative mould

III.7.c.vi Time management and additions

III.7.c.vii Retouching and tools

III.8 The production of other types of objects

III.9 Interpretation and discussion

III.9.a Implications of the introduction of the moulding technique

III.10 Identification of coroplastic workshops by different techniques

III.10.a The Workshop of the White Clay

III.10.b The Workshop of the Convex Back

III.10.c The Workshop of Straight Reworking

III.10.d The Workshop of the Chubby Faces and the One Pendant Necklace

III.10.e The skills of the coroplast

III.11 The coroplastic exchange between Sicilian towns

III.11.a Terracotta production at the kerameikos of Selinous and workshops in Akragas

III.12 Conclusions

IV Technically and iconographically defined typology

Group 1

Group 2

Group 3

Group 4

Group 5

Group 6

Chronological overview of the groups

V Conclusion

V.1 Concerning literary sources

V.2 Concerning iconography

V.3 Concerning production techniques

V.4 Concerning meaning and use

Bibliography

Catalogue

How to use the catalogue

Overview of the locations and contexts of findspots for figurines

Abbreviations/references for museum collections with figurines from Akragas

Type A: Argive Type (no.1‑2)

Type B: Face-moulded figurines (no.3‑7)

Type C: block-like figurines (no.8‑64)

Type D: Some characteristic faces and standing figurines (65‑70)

Type E: Imported figurines with rounded shapes, and objects inspired by them (71‑76)

Type F: Exceptional objects (77‑86)

Type G: Standing group (87‑97)

Type H: A variety of pendants (98‑106)

Type I: The same head, a different body (107‑114)

Type J: A patterned polos (115‑137)

Type K: The outlined-throne throne group and some similar figurines (no.138‑153)

Type L: other polos-wearing heads (154‑170)

Type M: The chubby face (171‑184)

Type N: A new hairstyle and widened polos (185‑197)

Type O: Seated on the left shoulder (198‑200)

Type P: Earrings (201‑202)

Dr. Gerrie van Rooijen

Gerrie obtained a Bachelor’s degree in Classics and a Master’s degree in Archaeology, specialising in Mediterranean Archaeology. She is fascinated by both the literature and the material culture of Antiquity, with a special interest in sculpture. In 2017 she published the first results of an archaeological experiment regarding the terracotta figurines from Akragas in an article titled Figuring out: coroplastic art and technè in Agrigento, Sicily: the results of a coroplastic experiment, published in Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia 47 (Van Rooijen et al. 2017, 151-161). Meanwhile she teaches Ancient Greek and Latin Languages and Culture at a high school.

Abstract:

The terracotta figurines from Akragas (Agrigento) with their chubby faces, splendid furniture, and rich adornments, depict a prosperous life in the late sixth and early fifth century BCE. The extensive jewellery on the figurines contains strikingly large fibulae appliques fastening pectoral chains with several sorts of pendants. They are modelled after existing items. The form of the jewellery items changed fast, influenced by different peoples and changing fashions, which can be compared with representations of jewellery and fashion on coins of the same period from Syracuse.

In contrast, the body of the figurines remained armless and abstract for some time, nor does it express its gender. The block shaped, sloping upper body might have originated with aniconic objects, but suggests here a seated person, covered with a rectangular apron on the front. In contrast, the face is detailed, and often crowned with a specific headgear, the polos. The Archaic smile reveals Greek influence on its features.

An archaeological experiment in which figurines and moulds were reproduced revealed their production process. By combining data from the experiment with an analysis of their iconographic features, most of the figurines studied can be shown to have been designed and produced locally. The moulding technique, introduced by newcomers to the city, provided for relatively cheap and rapid production of terracotta figurines. Local clay and marl are found near to the city, and its composition was found to be very suitable, due to its plasticity, fine structure and soft tone on firing.

Wooden figurines, the forerunners of the terracotta figurines, were used in the production of the moulds of their terracotta successors. The terracotta figurines developed to become more three-dimensional, so that they were able to stay upright unsupported. Objects and moulds were exchanged with the city of Selinous, resulting in variations of the standard and figurines with finely detailed faces.

Designing and dedicating these votive figurines, and possibly also jewellery, to a cult statue might have acted as a unifying element for the perhaps multi-ethnic society of Akragas. By means of these anthropomorphic female figurines, people gave shape to their origin and narratives, using old and new symbols such as the Phoenician crescent and the Greek satyr. Their cultural influences formed a new religious setting, helping to forge a new identity unique to Sicily. The prosperity expressed by these metal adornments, fits Diodorus Siculus’ description of Akragas as a rich city.

Contents

List of figures with references

I Akragantine figurines and their context

I.1 Introduction

I.2 State of research

I.2.a Identifying the figurine and the dedicants

I.2.b Proving literature right by the archaeological material

I.2.b.i Cult transfer and a prototype reconstruction

I.2.c Athena Lindia? Rhodian and Sicilian figurines compared

I.2.d Other views on identification and origin

I.2.e Oikist cult and cultural identity formation

I.2.f Intermarriage and gender

I.3 Aims and research questions

I.4 Method and archaeological theory

I.5 Research structure

I.6 Greek historiography on Sicily – some general remarks

I.6.a Mythical past

I.6.b Political setting

I.6.b.i The perception of ancient authors

I.6.b.ii Sicily in the account of Thucydides

I.6.b.iii The foundation of Gelas and Akragas

I.6.b.iii.1 Gelas

I.6.b.iii.2 Herodotus on Gelas

I.6.b.iii.3 Akragas

I.6.b.iii.4 Herodotus on Theron of Akragas

I.6.c Social and economic setting

I.6.c.i Diversity among the inhabitants of Sicily

I.6.c.ii Phoenicians

I.6.c.iii Prosperity of Akragas

I.6.d Religious setting

I.6.d.i Demeter and Persephone on Sicily

I.6.d.ii Temple building and politics

I.6.e Conclusions on the ancient literary sources

II Iconography of the figurines

II.1 Introduction

II.2 Aims

II.3 Method

II.4 The body

II.4.a The local tradition

I.4.a.i Arms and feet

II.4.b Imported and imitated images

II.4.c Upright

II.4.d From wood to terracotta

II.4.e An aniconic tradition

II.4.f Gender

II.4.g Practical implications of the figurines’ form

II.4.h The form of the figurines and their role as votives

II.5 Head and face

II.5.a General shape and expression of the face

II.5.b A personal expression

II.5.c Cultural influences

II.5.c.i Noses

II.5.c.ii Mouth and chin

II.5.c.iii Eyes

II.5.c.iv Ears

II.5.c.v Hair

II.5.d Gender

II.6 Dress and personal adornment

II.6.a The apron

II.6.b Non-Sicilian garments

II.6.b.i The undergarment

II.6.c Cultic dress

II.6.d Footwear

II.6.e Headgear

II.6.e.i Veil

II.6.e.ii Polos

II.6.e.iii The meaning of the polos and veil

II.6.e.iii The headdress as an indication of marital status

II.6.f Fibulae

II.6.f.i Interpretation and comparison with real-life objects

II.6.g Pectoral bands and pendants

II.6.g.i Akragantine pendants

II.6.h.ii Linked to the locals: pectoral bands

II.6.h.iii Discs and crescents

II.6.h.iv Figurative pendants

II.6.h.v Other beads and pendants with their real-life counterparts from other sites

II.6.h.vi Comparison with other cultures

II.6.h.vii Cultural exchange

II.6.h.viii Function and meaning

II.6.h Other jewellery

II.6.h.i Ear studs and earrings

II.6.h.ii Bracelets

II.6.h.iii Necklaces and hairbands

II.6.h.iv Comparison with korai jewellery

II.6.i Gender, identity and the display of wealth

II.7 Furniture

II.7.a From bench to throne

II.7.a.i The footstool

II.7.b The origin of the represented chair shapes

II.7.b.i Greek chairs: thronos and klismos

II.7.b.ii Thrones and lions

II.7.b.iii An enthroned couple

II.7.c Gender and identity

II.8 Conclusions

III The technology of Akragantine figurines

III.1 Introduction

III.2 Aims of technical research

III.3 Method: An archaeological experiment with analogue reconstruction

III.4 Interpretation and the chaîne opératoire approach

III.5 The general production process

III.5.a Object categories

III.5.b Solid objects and plaques

III.5.c Description of the steps in the production process

III.6 The coroplastic experiment

III.7 Results of the experiment and comparison with features of the original objects

III.7.a Step 1: The clays used in Akragas

III.7.b Steps 2 and 3: Choice of patrix and creating the matrix

III.7.c Step 4: Aspects of the shaping process and related items

III.7.c.i Making the front of the figurine

III.7.c.ii Making the back of the figurine

III.7.c.iii Making an extra rim

III.7.c.iv Drying and deformation

III.7.c.v The derivative mould

III.7.c.vi Time management and additions

III.7.c.vii Retouching and tools

III.8 The production of other types of objects

III.9 Interpretation and discussion

III.9.a Implications of the introduction of the moulding technique

III.10 Identification of coroplastic workshops by different techniques

III.10.a The Workshop of the White Clay

III.10.b The Workshop of the Convex Back

III.10.c The Workshop of Straight Reworking

III.10.d The Workshop of the Chubby Faces and the One Pendant Necklace

III.10.e The skills of the coroplast

III.11 The coroplastic exchange between Sicilian towns

III.11.a Terracotta production at the kerameikos of Selinous and workshops in Akragas

III.12 Conclusions

IV Technically and iconographically defined typology

Group 1

Group 2

Group 3

Group 4

Group 5

Group 6

Chronological overview of the groups

V Conclusion

V.1 Concerning literary sources

V.2 Concerning iconography

V.3 Concerning production techniques

V.4 Concerning meaning and use

Bibliography

Catalogue

How to use the catalogue

Overview of the locations and contexts of findspots for figurines

Abbreviations/references for museum collections with figurines from Akragas

Type A: Argive Type (no.1‑2)

Type B: Face-moulded figurines (no.3‑7)

Type C: block-like figurines (no.8‑64)

Type D: Some characteristic faces and standing figurines (65‑70)

Type E: Imported figurines with rounded shapes, and objects inspired by them (71‑76)

Type F: Exceptional objects (77‑86)

Type G: Standing group (87‑97)

Type H: A variety of pendants (98‑106)

Type I: The same head, a different body (107‑114)

Type J: A patterned polos (115‑137)

Type K: The outlined-throne throne group and some similar figurines (no.138‑153)

Type L: other polos-wearing heads (154‑170)

Type M: The chubby face (171‑184)

Type N: A new hairstyle and widened polos (185‑197)

Type O: Seated on the left shoulder (198‑200)

Type P: Earrings (201‑202)

Dr. Gerrie van Rooijen

Gerrie obtained a Bachelor’s degree in Classics and a Master’s degree in Archaeology, specialising in Mediterranean Archaeology. She is fascinated by both the literature and the material culture of Antiquity, with a special interest in sculpture. In 2017 she published the first results of an archaeological experiment regarding the terracotta figurines from Akragas in an article titled Figuring out: coroplastic art and technè in Agrigento, Sicily: the results of a coroplastic experiment, published in Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia 47 (Van Rooijen et al. 2017, 151-161). Meanwhile she teaches Ancient Greek and Latin Languages and Culture at a high school.

-

Digital & Online access

This is a full Open Access publication, click below to buy in print, browse, or download for free.

-

Buy via Sidestone (EU & UK)

-

Buy via our Distributors (WORLD)

For non-EU or UK destinations you can buy our books via our international distributors. Although prices may vary this will ensure speedy delivery and reduction in shipping costs or import tax. But you can also order with us directly via the module above.

UK international distributor

USA international distributor

- Browse all books by subject

-

Search all books

We will plant a tree for each order containing a paperback or hardback book via OneTreePlanted.org.

You might also like:

© 2025 Sidestone Press KvK nr. 28114891 Privacy policy Sidestone Newsletter Terms and Conditions (Dutch)